2023.02.03

CULTUREInternational Collaborative Productions Generate Art through the Process of Working to Understand Different Cultures

Performance of the international co-production play “Lear” (September 1997, THEATRE COCOON at Bunkamura in Tokyo). Photo: YAKOU Masahiko

The Japan Foundation has been involved in many overseas performances of Japanese performing arts, performances of overseas productions in Japan and the production of international creations. Common across all of these efforts is the promotion of cross-cultural understanding and the development of trust amongst performing arts professionals.

International creation in the performing arts is an area in which the process of mutual exchange and interaction is very visible, when compared to the Japan Foundation (JF)’s other cultural projects. The conflicts and camaraderie that arise in the process of creating a single work of art serve to deepen people’s understanding of different cultures and cultivates trust between artists.

Since the 2010s, the advancement of globalization has led to the international collaborative creation of a diverse range of performing arts, including contemporary theater. One production that has garnered a great deal of attention is “Pratthana – A Portrait of Possession” (hereafter “Pratthana”), which made its world premiere in Thailand in 2018. “Pratthana” was organized primarily by JF’s Asia Center, which was established in 2014, and was written and directed by playwright OKADA Toshiki, director of the theater company chelfitsch. This was not an original play by Okada, but instead a stage adaptation of a semi-autobiographical, full-length novel by Uthis Haemamool, one of the leading writers of Thai contemporary literature. By the time that he wrote “Pratthana,” Okada himself had already had success with overseas performances of his own plays. With “Pratthana,” however, the emphasis was on “not only adapting this piece into a play, but also developing an exchange and devising process at the same time.” As such, he spent several years on discussions with the author and on on-site research, developing a close spirit of collaboration between the Japanese and Thai staff. This work was performed in Paris at “Japonismes 2018” and in Japan at “Asia in Resonance 2019,” and has won major theater awards in both Japan and Thailand.

Performance of “Pratthana – A Portrait of Possession” at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2018. Parisian audiences were captivated by the four-hour long epic. Photo: Takuya Matsumi

ATPA as a Chance for Understanding Japan within Asia

Regarding “Pratthana,” UCHINO Tadashi, theater researcher and professor of Gakushuin Women’s College, wrote on the website of the Asia Center, stating: “This work was the culmination and natural extension of the Japan Foundation’s efforts, over many years, to produce a variety of international creations with teams in Asia.” And indeed, without JF’s long history of working on various cultural projects in Asia, this work may never have come to fruition.

One of JF’s founding objectives is to make a contribution to the world’s cultures. Thus, since its early days, JF has worked not only to introduce Japanese culture overseas, but also to introduce foreign cultures within Japan. Asian Traditional Performing Arts (ATPA), a project that began in 1974 and ended in 1987, was an early example of these efforts. At the time, Japan had become an economic superpower, and with the country’s increased responsibility on the world stage, Japanese society was beginning to realize the importance of both contributing culturally to the international community and strengthening relations with Asia. ATPA was conceived as a long-term project to introduce Japanese audiences to traditional Asian performing arts—something that they previously had very few opportunities to engage with—in a systematic manner. Each cycle of the project comprised three years, with research, seminars/performances, and creating archives each comprising one year of the cycle. The goal was to promote mutual understanding between Japan and Asia.

Across its five cycles, ATPA engaged in the themes of musical instruments in Asia, the musical voices of Asia, Asian masked performance, itinerant arts, and expressions of love and prayer. There was an element of academic exchange in these installments as well, with experts and researchers conducting seminars and symposiums, in addition to the shows by the performers themselves. The emphasis when selecting the performing arts and performers to be featured through this project was on introducing a diverse range of Asian performing arts—both well-known and unknown—with a deliberate effort to avoid a more “festival-like” atmosphere. As such, the performing arts covered included a wide range of traditional music and dances ranging from those of Korea, China, Mongolia, and Southeast Asia to those of India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, and others.

The first cycle, “Asian Musics in an Asian Perspective,” which featured musical instruments, included performers of music from the Sunda region of Indonesia at a time when it was almost unknown in Japan. KOIZUMI Fumio, professor at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music (at the time), who was the supervisor for this cycle, wrote in the magazine “Kokusai Koryu” (International Exchange), published by JF, “In Malaysia, it took three days for the performers to make their way out of the jungle, carrying their sape (an instrument shaped like a biwa, or Japanese lute). It was through this experience that we learned that there could be such extraordinary music out there in the jungle, unseen and unheard.” JF staff, looking back on ATPA, said, “[In the fourth cycle, which focused on Korean performing arts,] we wanted to feature performing arts that had an explosive sort of energy, similar to but different from those in Japan, and introduce these not only just to people in Tokyo, but to a wide range of people across the country,” and, “The scale of the performances grew larger and larger with each cycle, and around the fifth cycle, Asian culture was becoming very popular in Japan. Reaction to the performances was so great that it gave us a real sense of accomplishment.”

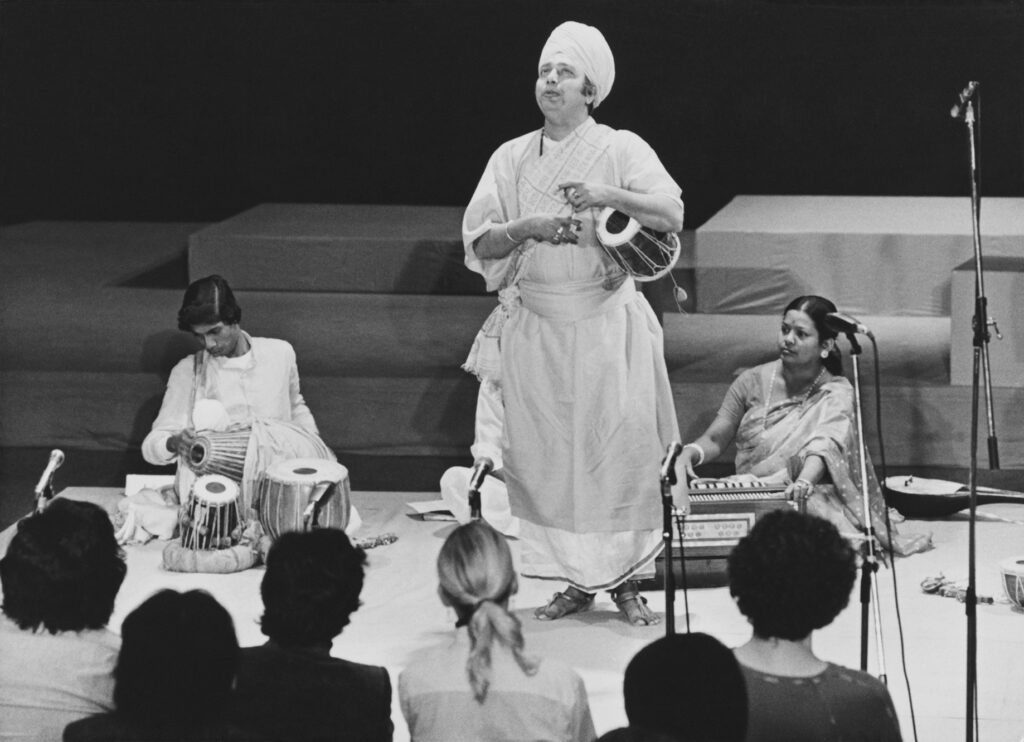

A performance of songs sung by the Baul mystic minstrels, who live in the farms of Bangladesh and the West Bengal region of India, in the second cycle of ATPA in 1978, titled “Musical Voices of Asia.” Photo: SEKIGUCHI Junkichi

ATPA’s legacy, in terms of passing down traditional Asian performing arts to later generations, was not limited to Japan, with reports of ATPA performances stored in the libraries of universities all around the world, and videos included in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution in the U.S. These reports and videos have become valuable cultural assets. ATPA ended in 1987, after creating opportunities for Japanese society to direct its attention to the diverse range of culture in Asia, and after successfully encouraging exchange between performers and researchers in different performing arts.

The 1990s saw an increased need to strengthen relations between Japan and Asia. JF thus independently planned and produced a variety of projects for mutual exchange, with the aim of expanding and deepening cultural relations with other countries in Asia, conducting their efforts primarily from the ASEAN Culture Center, which was established in 1990 within JF and integrated into the Asia Center in 1995 for further development. JF, which had gained considerable experience through its efforts in ATPA, had a new goal in the area of contemporary theater—to produce international collaborative works. The international co-production play “Lear” was conceived as a means to reevaluate the reality of Asian theater through the international collaborative production of a new work and to explore new possibilities. The emphasis was to be on creating together, not on simply introducing the different cultures to one another.

Work on “Lear” began in 1995 and it made its world premiere at the THEATRE COCOON at Bunkamura in Tokyo in September 1997, followed by a tour to Osaka and Fukuoka. The play received critical acclaim, with invitations to perform in Hong Kong, Southeast Asia and Australia, and at theater festivals in Berlin and Copenhagen, in 1999.

The Impact of “Lear”

The director of “Lear” was ONG Keng Sen, who at the time was an up-and-coming young director from Singapore. The project was a massive one, with performers selected from various genres, including contemporary theater, traditional theater (Noh, Peking opera), contemporary dance, contemporary music, and traditional music (gamelan, biwa), from six countries—China, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. The creative staff were also from many different countries. The play was written by playwright KISHIDA Rio based on Shakespeare’s “King Lear,” with Noh performer UMEWAKA Naohiko cast as Lear, and Peking opera performer Jiang Qihu cast as the eldest daughter. HATA Yuki, who at the time worked at JF and served as the producer of the work, said, “We believed that it was the process of artists of different cultures and methodologies coming together to create a single work that made international co-production so meaningful. In our discussions with Mr. Ong, we chose a work by Shakespeare instead of a work from a particular Asian country, so that everyone involved, from the production staff to the performers, would have the same amount of distance from the material. The goal was to borrow this composition of a father and daughter, the conflict and change that arises in the space between old and new, and by extension, explore a new theatrical language.”

It was in 1995 that Mr. Ong first discussed the project with Ms. Hata, around when he returned to Singapore after graduating with a master’s in performance studies from New York University. Looking back on that time, Mr. Ong said, “As soon as I heard about the idea, I remember thinking, ‘JF is attempting something new’, and that my experiences could be useful there. At the time, I was interested in ‘Asian-ness’ in the body and expressivity, relative to Western theatrical methodology. The challenge was less about reproducing costumes and behaviors or gestures on a superficial level, and more about figuring out ways to bring the various expressions inherent in Asian performing arts—rooted in customs and traditions across Asia—to life, and how to do so with Asian artists specifically, in a single stage production. For example, in depicting the killing of the daughter on stage, I was inspired partly by the act of cutting the hair at the root of a ponytail, which in Thailand is associated with cutting the umbilical cord of a baby. With performers and staff from such diverse backgrounds coming together to create this stage production, I thought long and hard about how these different forms of expressivity, which have been passed down throughout Asia, could best be communicated to people of different cultures and generations.”

Rehearsal of “Lear” in Tokyo. Mr. Ong said that producing an international collaborative work was not an easy task. “Different cultures had different expectations about how to work, how to rehearse, and the way the different schools of performing arts rehearsed or the amount of time they’d spent on rehearsal was also different. So, we did experience a lot of challenges once rehearsal actually started.” Photo: Shinji Hosono

The act of producing an international collaborative work, with performers of different languages and backgrounds, also makes differences in cultures and ways of thinking quite apparent. Mr. Ong said that, when faced with these differences, he emphasized the importance of the performers and others negotiating each other, in the vein of “This is my culture, and this is who I am as a person. “Lear” was not about providing information—it was about sharing knowledge. Knowledge here is based on one’s own body and experiences and includes the perspective of the artist. Here in the digital age, the trend—even in performing arts—is toward networking. But networking and art-making are different. Art-making begins when people negotiate each other with knowledge, and work and struggle to create something together. In “Lear,” the focus was on this process, with art considered a byproduct. Art involves a struggle to try to learn about other people, ourselves, and to finally create together. That’s something that is missing from cultural exchange more generally.”

Ms. Hata wrote in “Kokusai Koryu” the following: “As a collection of individuals from very different backgrounds, we were forced to confront others with a degree of openness that we had never taken on before.” And indeed, the project was an extraordinary challenge for the performers involved. The performers themselves have said that the continuous trial and error that occurred in the space between their own performing arts practice and the expressivity within the play led to some difficult situations. The act of creating this performance had a profound effect on the performers as well, with Jiang Qihu, who played the eldest daughter in play, saying, “Being able to participate in “Lear” had a massive impact on my journey as an artist afterwards.”

Mr. Ong Keng Sen. An internationally acclaimed Singaporean director, who also serves as artistic director of the theater company TheatreWorks. The founding festival director of the Singapore International Festival of Arts. Graduated with a Ph.D. in performance studies from the New York University Tisch School of the Arts. He has won many awards, including the Fukuoka Prize. Photo by Jeannie Ho

“Regarding the act of international co-production, people often say, ‘Collaboration is a noble effort and a luxury,’ but I personally feel that it’s actually a necessity… If we’re to solve some of the deep issues that exists between ethnic groups, we have to take on these multicultural efforts. This is why all of my work has been based on bridging the distance between cultures, and not just on appealing to aesthetic sensibilities,” Mr. Ong once said in the “Asia Center News” magazine, published by JF. “Lear” became a historical work, referenced even today in papers on Shakespeare’s “King Lear,” and a milestone of international collaborative production. JF’s efforts in exploring the possibilities of international collaborative works will continue.

【Related pages】

“Shunkan,” “Antigone,” “The Cherry Orchard,” Expanding the Circle of Excitement beyond Language Barriers

Sharing Japan’s Quintessential Stage Performances Online to Every Corner of the World